Subscribe to our newsletter

When Scientific Fraud Isn’t Fraud: How Both Researchers and Publishers Can Help Prevent Retractions – A Guest Blog by Tara Spires-Jones

Dr Tara Spires-Jones is a Reader and Chancellor’s Fellow at the University of Edinburgh working on Alzheimer disease research. She’s a member of the editorial board of several scientific journals including The Journal of Neuroscience and is reluctantly entering the world of public outreach.

Dr Tara Spires-Jones is a Reader and Chancellor’s Fellow at the University of Edinburgh working on Alzheimer disease research. She’s a member of the editorial board of several scientific journals including The Journal of Neuroscience and is reluctantly entering the world of public outreach.

In the last few weeks, peer-review and quality assurance in scholarly publishing (or rather its shortcomings) has come into focus again in the field of Neuroscience with the retraction of a controversial paper published in the Journal of Neuroscience in 2011 by the powerhouse lab of Virginia Lee and John Trojanowski (See Alzfroum news story). The authors were investigated by their host institution UPenn, who found that the errors in the published figures were not intentional and did not affect the conclusions of the paper. Despite this finding, the journal retracted the paper instead of allowing corrections, and further banned the senior authors from publishing in the journal for two years. This retraction highlights the wider problem of quality control of scientific papers. I have painful personal experience of this problem, which in light of this recent controversy, I am drudging up to try and make a few points about how we can avoid publishing these types of mistakes in the future.

The most devastating feeling in my scientific career, worse than getting rejected for major grants, dropping an expensive piece of equipment, or realizing that a box of irreplaceable samples has been ruined, was being accused of fraud. This accusation was from an anonymous blogger who had discovered errors in two papers on which I was a co-author. We published errata for these papers to correct the mistakes, both of which we tracked back to clerical errors in preparing multiple revisions of the manuscripts. All of the primary data and the analyses were sound, and our conclusions unaffected by the mistakes. We work incredibly hard validating our experimental protocols, performing umpteen control experiments, blinding the data for analysis, lovingly storing all primary data on servers backed up to a different building in case one building burns down, etc. So how did a group of such careful scientists publish not one but TWO papers containing errors in the figures, and what can we do to avoid this in future?

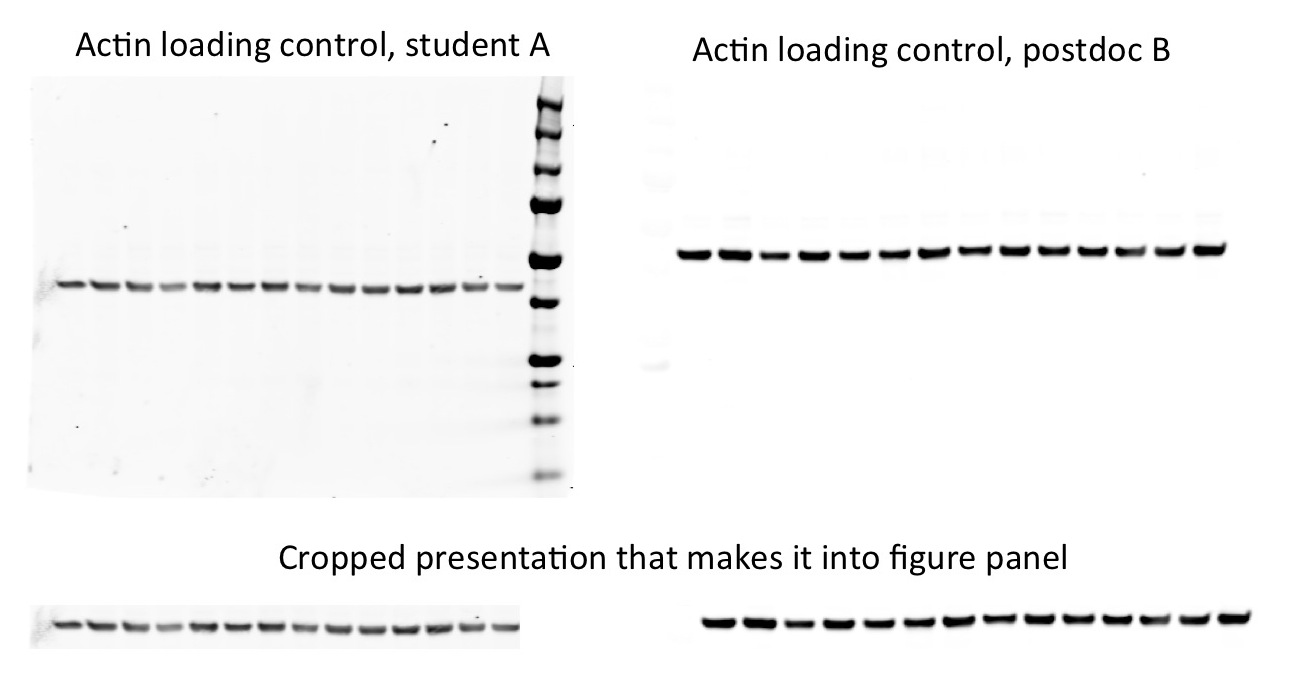

First, for those of you on the other side of the publishing fence, let me tell you what a Sisyphean task it is to get a paper published. Here is the rundown of a typical publishing experience: submit to journal A, they reject without review after a month or so. Submit to journal B, they have it reviewed, send it back two months later, asking for revisions. We do more experiments and send it back to journal B six months later. They then reject it so we re-format and send to journal C who review and ask for more changes (with another delay of a couple of months). We then do more experiments, revise again and journal C finally accepts the paper. In this example, we have gone through five major revisions of the paper over the course of a year, all of which involve moving the figures around. This figure rearrangement is where mistakes can easily creep in. Take a look at these examples of loading controls for Western blots from different experiments.

Not too different, right? Adding to the challenge, , figures often have to be placed at the end of manuscripts, making it harder for both authors and reviewers to keep track. And to make matters even worse, strict, over-small figure size limitations mean that we often present cropped versions of images simply to save space. Even with careful tracking of where each panel of each figure comes from, it is easy to see how clerical and formatting mistakes slip through the net.

So what are we doing about this? I recently started a new lab at the University of Edinburgh and with a clean slate, instituted several lab policies for data management. We now use electronic lab notebook software. I chose eCAT (now RSpace), because it’s locally supported by the University. I have colleagues who use and like other programs such as Labguru. The electronic notebook for the whole lab allows me to easily search for experiments and importantly, after students and postdocs move on, I can find individual experiments without wading through years of paper notebooks or spreadsheets. When preparing figures, I can link them to the raw data files. As part of the wider push for data sharing, we are also starting to collect all of the raw data that goes into each published paper and upload it to our university data repository. On a practical level, this means we are able to keep better track of each figure and what data were analysed to make it, making it less likely that we will make mistakes in manuscript preparation.

Those are a few of the things we as scientists are doing, but the publishing industry can also play a role in improving quality control. Two of the biggest values that publishers add to the scientific endeavour are the cultivation of peer review and selection of the best papers to publish. Peer reviewers and editors should really be catching this type of error in figures (full disclosure here, I am also a frequent peer reviewer and editorial board member of several journals including J Neurosci). There are initiatives by publishers that are helpful such as requiring the full raw images as supplemental material. This is particularly useful when only a cropped version is presented in the full text article. Many journals also require the uploading of raw data for some (or all in the case of PLoS) types of datasets, particularly for genomics, proteomics and other “omics” technologies. Giving the reviewers and editors the opportunity to view the raw versions of figures and data could be quite helpful, although I’m hating myself a little bit already for suggesting this and heaping more things to review onto my desk.

Looking only a little further into the future, the more that publishers are able to support researchers with information management tools, the more these technologies can be interconnected. One day hopefully soon, version controlled data sets and figures could be connected to the published article without requiring manual steps like copy and pasting, that so easily lead to these final-step errors.

Clearly mistakes will continue to happen in publishing and as an individual scientist, I don’t have all of the answers to how to reduce these. Having said that, some of the new technologies and initiatives in data sharing and data management will unquestionably help researchers keep their data and figures in order. On the publishers side, there are lots of ways in which information handling might be improved between the bench and the article and there is plenty of room for publishers to help on this score. My appeal to publishers is to keep in mind that researchers want high quality data and are willing to work together to ensure we get it in publications.