Subscribe to our newsletter

#MeToo and the Scientometrics of Sexual Harassment

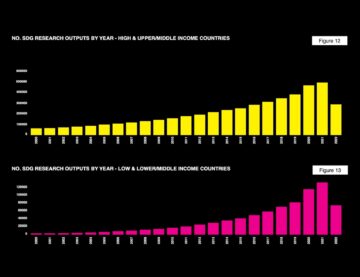

Earlier this month we released our report, Contextualizing Sustainable Development Research, which looked at research trends related to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) using our new SDG categorisation in Dimensions. Over the next few weeks we will be hearing about some of the ways that we can use data to monitor progress towards meeting these 17 SDGs set out by the UN. Our first article is from Mike Taylor, and looks at an aspect of research relating to SDG 5, Gender Equality.

Mike Taylor is Head of Metrics Development at Digital Science. Before joining us he spent many years working in Elsevier’s R&D group and in the Metrics and Analytics Team. Mike works with many community groups, including FORCE11, RDA and NISO, and is well known in the scholarly metrics community. He’s also notorious amongst the Oxford theatrical scene as an actor, producer and director with ElevenOne Theatre. In his spare time he provides the entertainment for many a hen night with the murder-mystery company, Smoke and Mirrors. Mike is studying for a PhD in alternative metrics at the University of Wolverhampton.

Mike Taylor is Head of Metrics Development at Digital Science. Before joining us he spent many years working in Elsevier’s R&D group and in the Metrics and Analytics Team. Mike works with many community groups, including FORCE11, RDA and NISO, and is well known in the scholarly metrics community. He’s also notorious amongst the Oxford theatrical scene as an actor, producer and director with ElevenOne Theatre. In his spare time he provides the entertainment for many a hen night with the murder-mystery company, Smoke and Mirrors. Mike is studying for a PhD in alternative metrics at the University of Wolverhampton.

MeToo and the Scientometrics of Sexual Harassment

Until the Harvey Weinstein scandal of October 2017, the field of sexual harassment will have been unknown to most academics and bibliometricians. Indeed, the fact that it is a known topic of funding and research – albeit on a very small scale indeed – will have largely been a mystery to most of us. A chance conversation with a colleague who wanted to look at the influence of feminist theory lead us to examine the field of sexual harassment, and the influence of the #MeToo phenomenon on research funding and focus. This sheds a particular light on the interaction between academia and society, the need for readiness and a willingness to adapt to new circumstances amongst the academic community, and the way in which social media can shape and communicate public discourse in a research field.

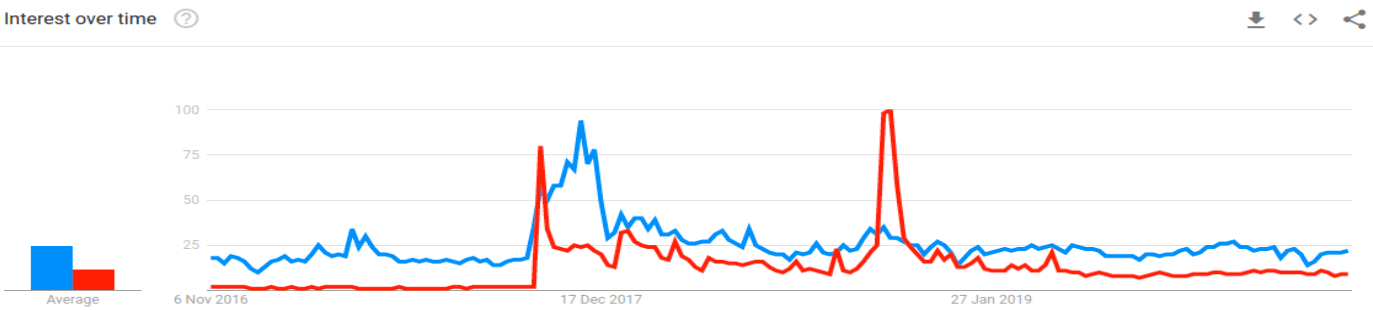

Examination of Google search engine queries for the terms “sexual harassment” and “MeToo” produces an interesting graph with several features. The two most prominent peaks for ‘MeToo’, a term that had previously not been widely used, occur in October 2017 and late 2018. Although queries around ‘MeToo’ fall quite sharply in both cases, it remains a substantial search query. The ‘MeToo’ phenomenon has had a clear impact in searches related to sexual harassment, boosting the number of queries by around 25% compared to the baseline average. It is interesting to note that the second peak in 2018 doesn’t have any effect on the volume of searches around ‘sexual harassment’, which remains relatively steady during this time.

Figure 1 Worldwide search engine results for ‘sexual harassment’ and ‘MeToo’

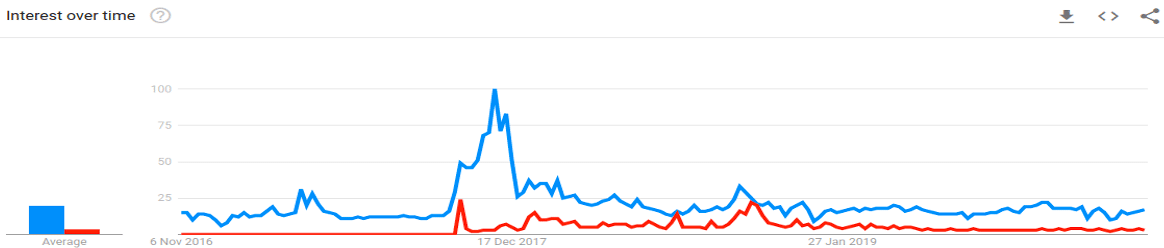

If we dive deeper into this data, we can start to make more sense of it. By filtering the data to show only results from the USA, the second peak disappears. We can clearly see the direct influence the volume of searches for ‘MeToo’ has had on the volume of searches for ‘sexual harassment’. Following an increased number of searches for ‘MeToo’, we see an even more dramatic increase in the number of searches carried out for ‘sexual harassment’. This trend is common for most European and predominantly English-speaking countries.

Figure 2 USA-located search engine results for ‘sexual harassment’ and ‘MeToo’

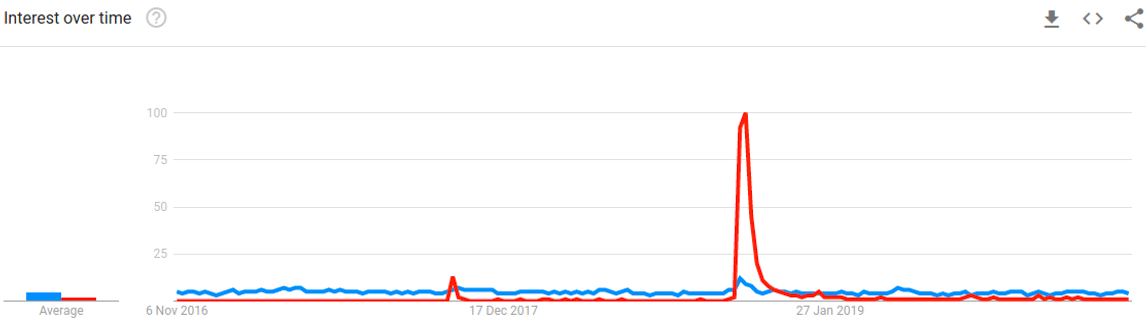

Figure 3 India-located search engine results for ‘sexual harassment’ and ‘MeToo’

So what about the second peak? Where does this come from? Further analysis reveals that the late 2018 peak in global searches was a down to separate wave of the #MeToo phenomenon which occurred in India. Although its impact on Google search volume was larger than the original October 2017 peak, it did not result in a long-term increase in searches for ‘sexual harassment’ in India, nor was there any sustained rise in the number of ‘MeToo’ searches in this country.

This analysis shows that the #MeToo phenomenon was a global phenomenon, but one that has had different qualities and different levels of impact in different countries around the world. In the USA, UK, and other countries, #MeToo appears to have unlocked a substantial discourse around sexual harassment; in other countries, it has not had that effect. Interestingly however, from a scientometric perspective, #MeToo has also had an additional effect: this social movement has stimulated explosive growth in research on sexual harassment.

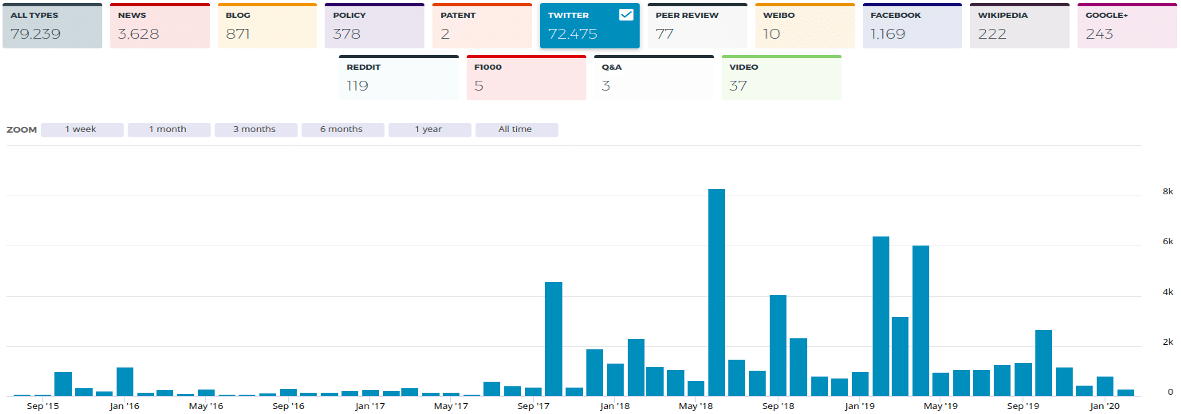

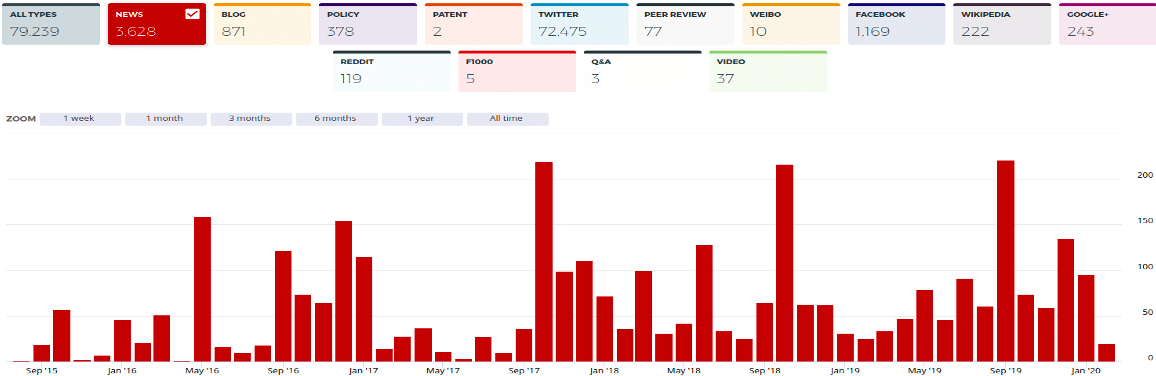

The altmetric data for research in this space shows a number of interesting trends in discourse in this field, and in particular shines a light on activity within different communities. Using the Timeline feature in Altmetric Explorer, we can see that the number of tweets linking to research being carried out in this area largely mirrors the volume of related searches in the USA: they rise dramatically in October 2017, and remain at this higher level. In this case, it is possible that the higher volume of research being published may lead to increased levels of Twitter engagement in itself.

Figure 4 Tweets linking to research about ‘sexual harassment’ and ‘MeToo’ in Altmetric

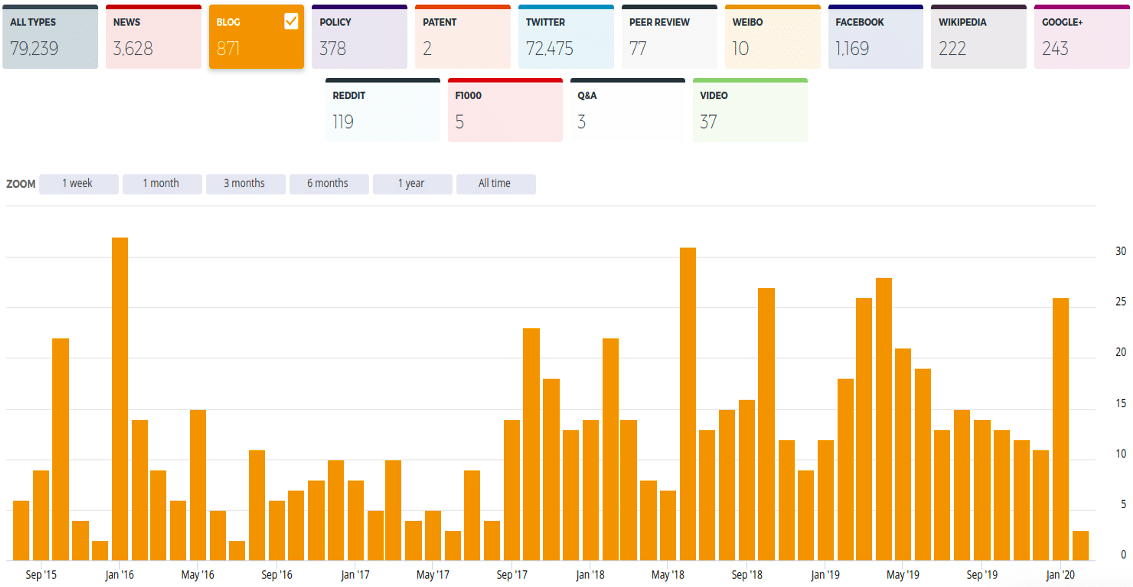

The number of mentions about this research in mainstream media and blogs shows a less dramatic trend, but nevertheless shows consistently higher coverage in the months following October 2017. Interestingly, it also shows a separate phenomenon, not easily visible in these graphs due to lack of space; the growth of discourse about this research area in the two years preceding the Weinstein scandal. This growth is reflected in the volume of research output in the years 2015-2017 when research volume doubled, albeit from a very low number).

If you spend just a few moments looking at this research on the free version of Dimensions, you will have a good grasp of the nature of work being carried on in this space: very practical, multidisciplinary, and with a very strong focus on the downstream effects of sexual harassment on women, women’s careers, professions, and societies. Likewise, by spending a little time on the blogs that were reporting the research in the years before 2017, you start to sense both the frustration and the anger experienced by people working in this space, but also the coherent and focussed nature of their work. Research published in the decade before 2015 is very different: although we hesitate to make judgements, it feels like a more coolly academic area of work.

Figure 5 Mainstream media linking to research about ‘sexual harassment’ and ‘MeToo’ in Altmetric

Figure 6 Blogs linking to research about ‘sexual harassment’ and ‘MeToo’ in Altmetric

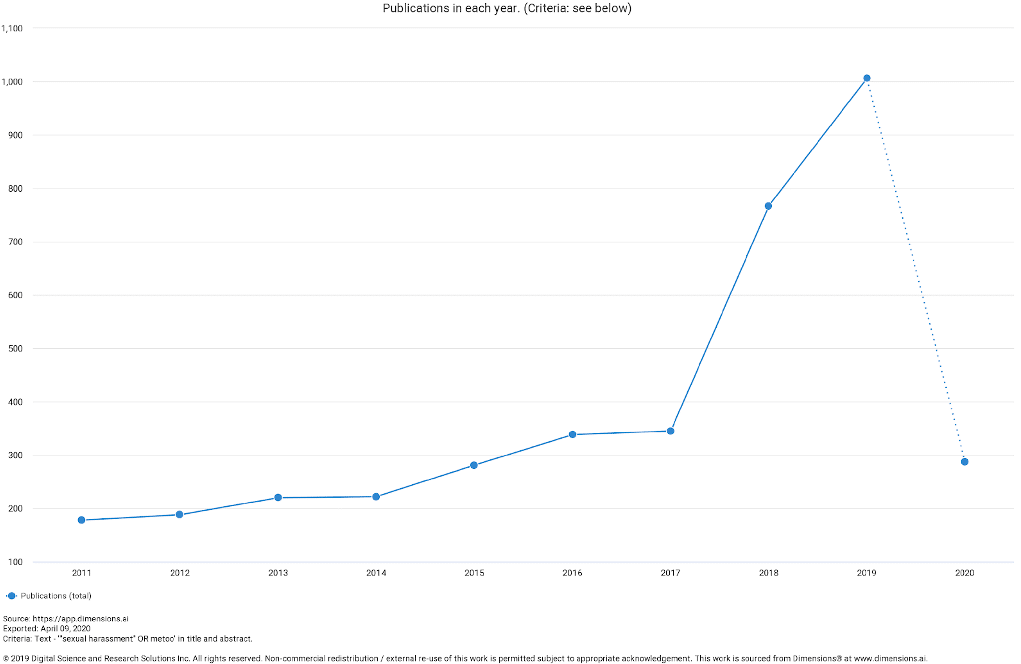

The altmetric data suggests that there is a shifting discourse and sense of rhetoric within this research community as it moves towards the formation of a unified community of people with shared interests; a proto-network of academics who are willing and able to address a real-world crisis with research. The publications output in Dimensions confirms this suspicion: we can see the growth in annual output of sexual harassment research up to 2017, and then the explosive growth in academic publications following the Weinstein scandal, rising from 500 publications a year to 5,000. Mendeley Readers suggests a similar growth in academic interest, presaging a substantial expansion in future citation rates and usage for this relatively small research community.

Figure 7 Publication growth for research in ’sexual harassment’ OR ‘MeToo’

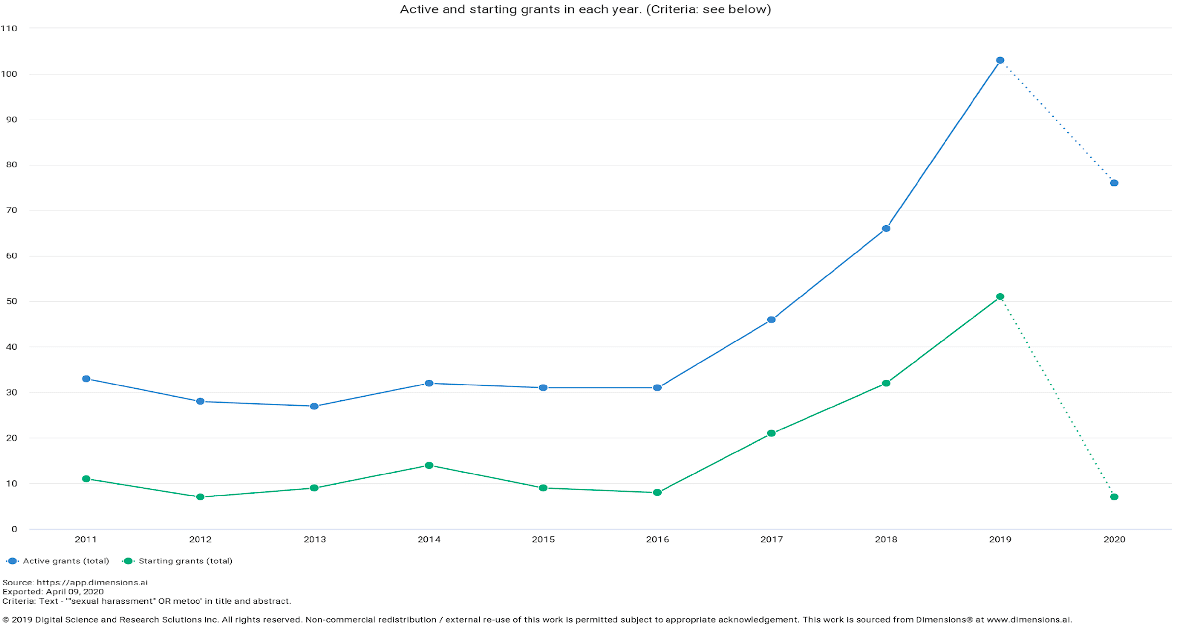

Figure 8 Research grants in ’sexual harassment’ OR ‘MeToo’

The annual rate of publications and readership has multiplied tenfold. A similar rise can be seen in the growth of research funding in this area, with total funds rising from $1.8M in 2014 to $6.3M in 2019 – a number already exceeded by an unprecedented $6.9M of funding in 2020.

The different pieces of research data available to us using Altmetric and Dimensions can be woven together to create a fascinating narrative of a small and previously poorly funded research topic. The years leading up to the events of October 2017 are characterised by a relatively small group of researchers, growing steadily, but able to connect their research with issues in the wider world, and with their research able to find an audience in both mainstream media and the blogosphere. In the aftermath of Weinstein, that community finds a new audience in the general public, who are willing and able to engage with existing research. This, in turn, enables academics to create more research, getting more attention from the public, from other academics and, crucially, in research funding.