Subscribe to our newsletter

Open Sesame! The Risks and Rewards of Open Data for Researchers

Jon Tennant is a PhD student based at Imperial College London, investigating extinction and biodiversity patterns of Mesozoic tetrapods – anything with four legs or flippers. Prior to this, there was a brief interlude where Jon was immersed in the world of science policy and communication, which has greatly shaped his view on the broader role that science can play, and in particular, the current ‘open’ debate. He tweets as @Protohedgehog, and blogs for the EGU.

Jon Tennant is a PhD student based at Imperial College London, investigating extinction and biodiversity patterns of Mesozoic tetrapods – anything with four legs or flippers. Prior to this, there was a brief interlude where Jon was immersed in the world of science policy and communication, which has greatly shaped his view on the broader role that science can play, and in particular, the current ‘open’ debate. He tweets as @Protohedgehog, and blogs for the EGU.

Open access is a done deal. There is a clear global recognition that free and unrestricted access to research articles is a good thing for everyone. However, the movement towards more transparent scientific communication is not resting on its laurels. There is a new frontier in open science and that is data. Funders are increasingly mandating that researchers make their primary data available so that it can be built upon, though it’s not all plain sailing. Many researchers remain unconvinced that it’s in their own personal interest to share their data. In a post last year in the Scholarly Kitchen, Kent Anderson laid out some of the risks as he perceives them as a publisher.

To help me write this post, Phill Jones of Digital Science put together some objections that he occasionally hears from those researchers who remain unconvinced. Below, I will explore and try to counter some of these frequently stated objections.

1) “If I make my data available, somebody will re-analyse it in order to undermine my conclusions. It’s easy to misrepresent data and I don’t want to make it easy for detractors to undermine my work unfairly.”

Raw data is the fuel of science. Re-analysing data and assessing conclusions forms one of the key pillars of research: reproducibility. Without making data openly available for assessment, research isn’t really research, it’s just anecdote. The debate that comes from the critical reanalysis of data and results is central to how science functions. We should embrace the increased visibility that opening up our data gives to all stakeholders involved in scholarly communications.

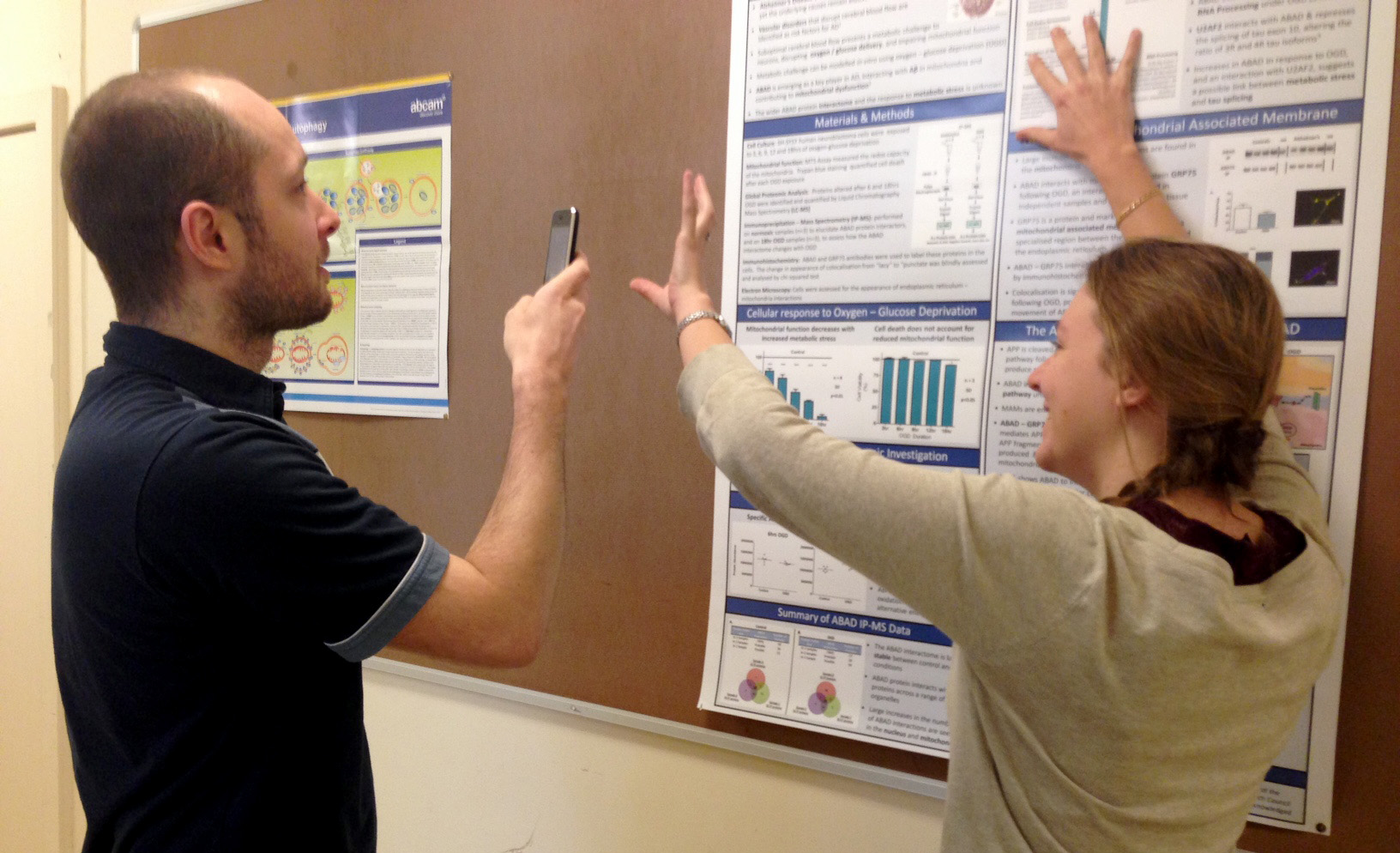

Developing upon research, whether to produce positive or negative results is an important way in which research progresses and knowledge accumulates. Furthermore, sharing your research data opens up more doors than it closes. It shows that you have confidence in your own work and have nothing to hide. It encourages scientific debate, scrutiny, and enquiry, and can lead to new innovations. From personal experience, I can also say that opening up my own data has enabled me to find new collaborators, enabling me to make a greater scientific impact.

It’s not about adding bricks to a wall – sometimes the wall has to be demolished to make way for a building. We shouldn’t be afraid to support researchers whose conclusions have subsequently been demonstrated to be incorrect. It’s OK to be wrong, and we should embrace this as a community.

2) “It takes me a long time to generate a data set. I frequently publish an initial analysis of data and then follow it up with analyses that are more in-depth or from a different perspective. If I publish my data, I loose control of it and somebody else might scoop me.”

This is where data citation comes in. The majority of data sharing platforms come with a Digital Object Identifier (DOI), or are licensed under a Creative Commons attribution license (CC BY), which means that data can be cited on the same level as research articles. This has yet to become widespread practice, but the more people that begin to cite data, the more common and accepted it will become. As a proponent of open science, I hope that one day soon, data citations will be considered just as valid as traditional article citations.

When your data is cited, you get additional credit for more research outputs than just a paper. If you’re into metrics, then the number of citations is a pretty important figure for an individual, which can play a role in funding applications, hiring, and promotion. A study by Heather Piwowar and Todd Vision shows that there is a clear citation advantage to making your data open. In addition to this, they found that this advantage persisted for years beyond the time period in which the researchers had maximally used their data to publish papers.

Some publishers are also now creating ‘data journals’. In these journals, data are published without any discussion or formal results. All this taken together, we are beginning to see a trend towards increasing reward for open data. For open science to move to the next level, the research community and funding bodies must recognise that data are at least as important as traditional research articles.

One possible solution to mitigate the risk of being ‘scooped’ is the creation of data embargoes, similar to the green open access embargoes that many funders and publishers have negotiated. An appropriate system of embargoes, where data is not released alongside a publication, but delayed for a suitable amount of time, would protect authors’ abilities to maximally exploit their own data for personal research and publication.

3) “The data that I have is in a highly specialized format that other people cannot necessarily read, let alone interpret. Aside from the fact that many repositories don’t accept my file, I hear that I have to make my data interpretable. I simply don’t have the time to process my data or convert its file type so that people outside of my field can take advantage of it.”

What I think is becoming clear is that community-dependent standards for data sharing simply do not exist. What would make this much simpler if guidelines existed to help researchers develop and construct their data in a manner that is interpretable and usable by external parties. Developing best practices for data reuse and sharing, including good metadata, common repositories, and proper citation for appropriate credit are all ways to try and achieve this.

There is an ever-expanding range of options for scientific data formats. Subject specific repositories, for instance often offer niche file support for specific disciplines. Institutional repositories are arguably lagging slightly in terms of file support, but some commercial offerings are highly flexible. Figshare, for example, will extend support for any file type upon request.

There are admittedly still more to discuss and several issues to explore. Questions regarding the opening up of commercially or medically sensitive, or industrially-funded, data are examples. Whether or not sensitive data are made openly available should be assessed on a case-by-case basis depending on the situation. There are also open questions surrounding data duplication and negative data, but I’ll leave those for a subsequent post.

Researchers all want to contribute to the global pot of knowledge, that’s why we do what we do. Let us return to and embrace this principle of open research, and make our data open – who knows what might be achieved, and who knows what might be lost by restricting access to it.