Subscribe to our newsletter

My Meta (Mis)Adventures with open access monograph metadata

Jen Slajus is the Client Sales & Marketing Manager for Longleaf Services.

Three years ago, my nonprofit publishing services company, Longleaf Services, a subsidiary of the University of North Carolina (UNC) Press, received a Mellon Foundation grant to develop a digital-first open access pilot program to allow university presses to publish history monographs openly.

It turns out that producing open access monographs and making content universally available can be significantly more challenging than creating paywalled print editions; the fundamental concept of metadata standards breaks down when there are more than one set of them; and sometimes the only way to progress is to dig into the weeds and work tête-à-tête with your partners. After publishing 35 open access monographs and with more in the hopper, now is a good time to reflect on lessons learned.

The Sustainable History Monograph Pilot, or “SHMP,” program’s primary goal was to create an economical and transformative open access publishing process. We would use affordable, third-party, web-based workflow tools that could be adopted widely, thereby enduring beyond the initial three-year funding period and helping to prove the long-term merit and viability of open access books in the real world of mere mortals, not just the (theoretical-minded) OA Gods. ¡Viva la Revolución!

Three goals were metadata related:

1) Devise and propel a comprehensive set of OA monograph metadata standards across our two dozen SHMP-participating presses. Factor in requirements from open access and institutional platforms in the humanities: OAPEN, Internet Archive, JSTOR, ProjectMUSE, and EBSCO. Emphasize to publishers, through our standard requirements, that robust metadata is the key to online discoverability and the best way to reach the widest audience.

2) Create a budget-friendly, highly automated method of collecting metadata from publishers and disseminate their data, book cover, and electronic content files to the open access platforms listed above. The process should seamlessly fit into presses’ existing data management workflow.

3) Post-publication, analyze the impact of SHMP titles both quantitatively and qualitatively.

We had our mission.

Fast forward a blurry month or two of immersion into open access monographs, gathering metadata requirements from platform partners and industry standards from Editeur, who provide these basic FAQs. I blended these with several ONIX snippets and seasoned with my own book industry experience and best practices to produce a SHMP Metadata Guide, which I gleefully shared with all 23 presses.

Crickets.

The hurdles

Did they see these requirements as being extra-ordinary? Or somehow generating that. much. more effort?

It quickly became apparent that the CoreSource metadata and digital asset management system already in use by a number of university presses, which we had craftily planned to use to auto-distribute books’ content and metadata files to platform partners, didn’t support a number of required open access attributes via industry-standard ONIX 3.0 xml files. (Breathe.)

Missing attributes included a secondary publisher to accommodate the open access funding body, the open access license link in its proper ONIX place, the contributor-level ORCID, or ISNI, and, the final nail in the coffin: the <UnpricedItemType> to identify an OA monograph’s $0.00 retail price. (CoreSource is planning to address these gaps in 2022.)

It turns out that EBSCO and several other major platforms built around selling books also don’t accept items with prices below $0.01, so we were unable to send them metadata directly either. Fortunately, OAPEN pushes our data and content files to them through a backdoor. Another jaw-dropper: Overdrive, the leading digital content provider to public libraries in the US, doesn’t accept open access books. And Amazon will only feature a free Kindle version when the publisher also offers a for-sale print version.

As John Sherer, the UNC Press Director and driving force behind SHMP, puts it: “Our systems (CoreSource, Firebrand, Virtusales, etc.) were basically built to help Amazon sell our books. Even in the UP world, we designed metadata to help EBSCO, ProQuest, MUSE, JSTOR sell our books. They were designed for discoverability within walled gardens owned by sellers of content. Not surprisingly, these same systems are ill-equipped to spread metadata for free content. Metadata distribution is essentially free in paywalled models because the companies that distribute metadata will recover their costs through commissions on sales. When those incentives are removed, the existing system breaks apart, and we are in the ironic position of potentially doing a worse job of distributing free content than we do paywalled.”

For the same reasons, many of the participating presses also struggle to market their open access monographs. Should they include them along with their for sale books in new release catalogs even though some major outlets won’t feature them? And do they risk cannibalizing their print edition sales?

A manual workaround

We had a goal of publishing 75 titles over three years and, since we wanted to apply Mellon money to the production of the books themselves, we went old-school: files loaded into DropBox and manually uploaded onto each platform, eyeballing whatever ONIX xml files the presses could provide to “validate” inclusion of all required metadata; returning them for revision, as needed. They ultimately own their metadata for all editions and will need to send these title records to Amazon and all of their other retailing, data aggregating, library, and institutional partners.

Even today, a few of our SHMP presses struggle to meet our ONIX 3.0 file requirements, relying on antiquated legacy title management systems that deal only in ONIX 2.1 files, which don’t support all required open access attributes. A couple of presses don’t have a direct relationship with Crossref to secure their own DOIs, since their primary focus continues to be paywalled print books, which keep their lights on and acquisitions flowing.

When a publisher is unable to meet our basic open access data requirements and asks to provide these in an Excel file (or, gasp, email), we make do with the core data that allows our partners to ingest these titles and then rely on the natural interconnectivity of web platforms, plus the secret world of data-embellishing librarians, to enrich these titles over time. And, of course, we all keep asking system providers to step up and support all OA attributes once and for all.

The state of play today

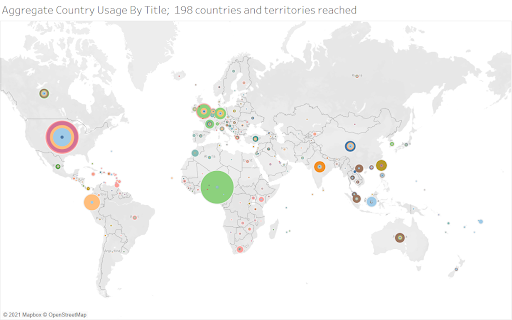

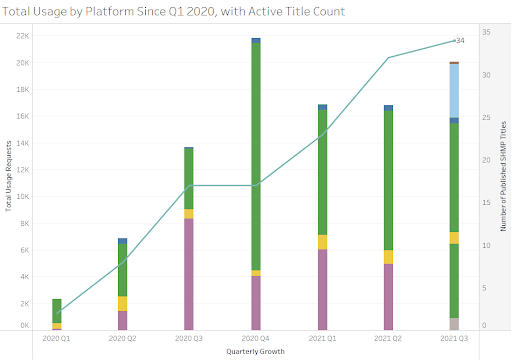

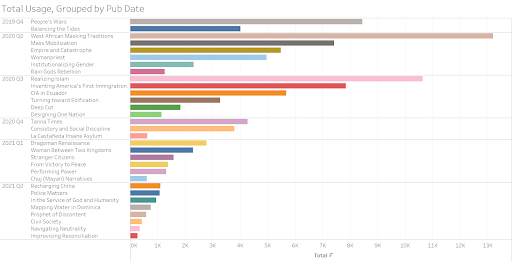

By the end of September, 2021, we have helped 16 presses launch 34 SHMP open access books and have added one open access platform to our distribution mix: ScienceOpen. According to our records, these books have gleaned 100,000 Total Item Requests, Views, Resolutions, downloads, printings, emails, clicks, hits, touches, —what precisely to name these ‘engagements’, especially when each one may mean interacting with the full text or just a piece of it, such as a cover image, page, or chapter? (See References and Other Helpful Resources on OA Monographs below) — by readers in nearly 200 countries and territories across these six OA platforms: OAPEN, Internet Archive, JSTOR, Project MUSE, EBSCO Faculty Selects, and ScienceOpen, plus Amazon and a smattering of publishers’ own digital platforms.

Soliciting, collating, and analyzing these usage data has been another meta adventure. Of course, had we more resources, we would have deployed a SQL database on an FTP server as our usage data repository and developed APIs with participating platforms. Instead, we consume sometimes inconsistent and often late emailed reports, perform manual page view counts, and run a mix of Access and Excel Power Queries that feed our single instance of Tableau.

We provide participating publishers aggregated usage updates monthly, as well as one- and two-year anniversary summaries of their titles’ impact. We plan to offer comparisons between these digital open access versions and their for-sale print siblings that are published three + months later, to examine the so-called cannibalization effect, as soon as we are able to collect enough data to make sense of it.

Authors have expressed amazement at the speed at which the entire SHMP publishing workflow was executed, gratitude at the opportunity to reach, or expand, their intended audience by providing a free ebook option, curiosity at the unique global and institutional reach their digital monograph achieves, and a deeper understanding and appreciation of open access as a legitimate publishing model and one that should be acknowledged as such during the tenure process.

We also receive the occasional personal note of appreciation via our SHMP reader survey, the link to which is embedded in each ebook, like this one:

What is the name of the book you read/used?

Chuj (Mayan) Narratives Folklore, History, and Ethnography from Northwestern Guatemala

How easily can you normally access a university press monograph?

I can rarely access or afford books like this

Which of the following best describes you?

Other

If other, please describe…

Literacy Council volunteer, Adopt-a-Village in Guatemala (www.adoptavillage.com)

What are the chances that you will purchase a print edition of this book?

Unlikely

Where were you when you accessed this book?

Central America

So maybe the ultimate response to how impactful SHMP OA books have been in the real world: to some readers, free = priceless.

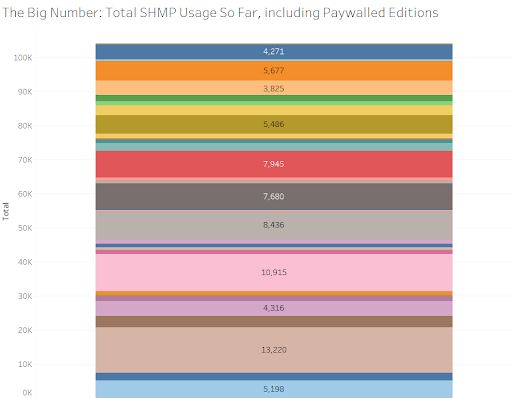

Sum: 104,046

Average: 2,972.74

Minimum: 54

Maximum: 13,220

Median: 1,375.00

References and Other Helpful Resources on OA Monographs:

- Open Access monographs in ONIX for Books FAQ

- COPIM and their blogs

- Scholarly Kitchen’s metadata articles including this recent one

- Project COUNTER The definition of COUNTER’s Metric Type that represents the number of times users requested the full content (i.e., full text) of an item. Requests may take the form of viewing, downloading, emailing, or printing content, provided such actions can be tracked by the content provider’s server.