A follow up to “WriteLaTeX for Research”

Foreword by John Hammersley: Ten years after he wrote the guest post “WriteLaTeX for Research” , we followed up with Mikhail Klassen, an early user of Overleaf, to find out what he was up to now, whether he still had his old research diary notes, and what further innovation he’s looking forward to in the decade ahead. Here’s what he told us…

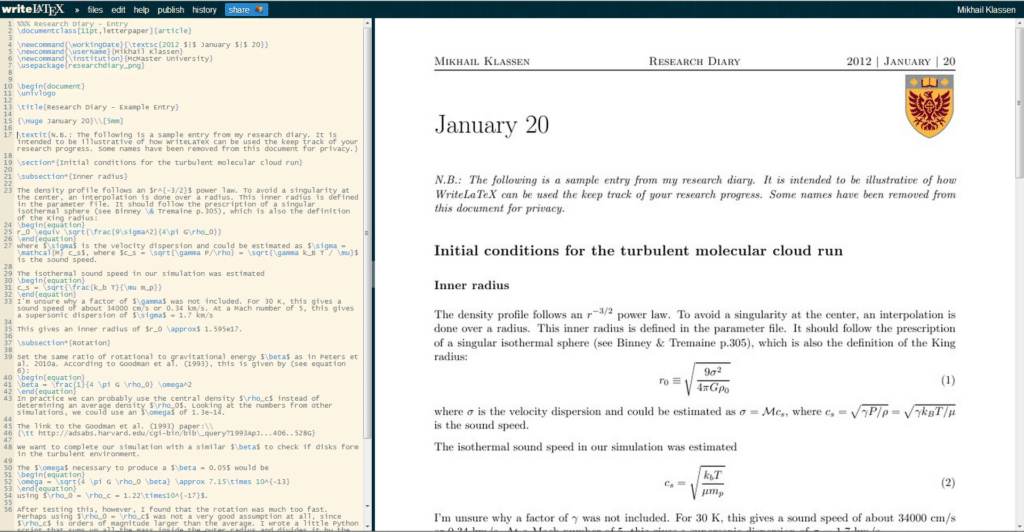

Ten years ago, in 2013, I wrote about using WriteLaTeX (now Overleaf) for academic research. At the time, I was a graduate student in computational astrophysics at McMaster University, studying the formation of massive stars using large-scale computer simulations. In addition to doing cutting-edge research, I was also trying to build good habits as a scientist, which meant keeping detailed notes and tracking experiments.

My early research notebook software

Research notebooks have been used by scientists for centuries, but I wanted something digital. Whatever solution I settled on, it needed to support LaTeX to properly typeset any equations, of which there were many. The LaTeX markup language is familiar to any physicist that has ever had to publish a paper, and many journals expect scientists to submit manuscripts typeset in this way.

This being 2013, and not initially finding any tools I liked, I created my own research notebook software that consisted for a collection of templates and scripts. To this day, it’s still one of my most popular open-source repositories on GitHub. But maintaining the software myself, including the build environment, was cumbersome and a distraction. That’s when I discovered WriteLaTeX, and befriended the cofounder, John Hammersley.

My research diary templates were added to WriteLaTeX’s template gallery so that others could benefit and I shared about my experiences in the blog post John mentioned in his foreword.

In 2016, I defended my PhD and left academia. With my final research papers published, I archived my research notebooks and other artifacts to my personal computer’s hard disk and moved on. Today I work in applied machine learning, and like John, founded my own start-up!

Paladin AI – founding an aerospace start-up

After graduating, I cofounded a technology start-up in the aerospace sector called Paladin AI. Together with a team of software developers and data scientists, we developed an adaptive learning platform for helping commercial pilots train more efficiently on flight simulators.

I still think about my time as a young graduate student fondly. There’s something exciting about going to work every day with the objective of learning something new and sharing it with the world. It’s an attitude I try to take with me into my professional life today.

Another habit is trying to keep up with scientific developments in the world today, especially in my field of machine learning. The most recent paper I read was a computer vision paper DINOv2: Learning Robust Visual Features without Supervision by Oquab et al. at Meta AI Research. These technologies are set to revolutionize the way AI’s understand their environments, and will play a key role in robotics and augmented reality devices.

Keeping up with artificial intelligence breakthroughs today can feel like a full-time job. It helps to follow other thought leaders in the space who share the latest research developments with their audiences. Some of my favourites are Two Minute Papers by Károly Zsolnai-Fehér on YouTube, Sebastian Raschka and Eric Vyacheslav on LinkedIn, and Roberto Nickson on Instagram.

I no longer keep a research diary and haven’t written an academic paper since 2016, though I miss it sometimes. I will keep other notes and journal using tools like Notion, and I have a Google Doc that I use to log the books I read going back to 2012.

Looking forward to the decade ahead

When I think about the future, there’s an idea that I keep thinking about, which is what the convergence of AI and the practice of science will look like. Large language models embedded into tools like ChatGPT have the potential to become a source of on-demand knowledge and intelligence.

In the early modern period, it was possible for a scientist to master multiple fields and make cutting-edge contributions. In today’s world, to attain a PhD means subspecialization in a narrow niche unfamiliar to other scientists, even many within your broader field. It has become impossible to keep up with the flood of new research being published every day. However, it could theoretically be possible for a powerful language model to read all posted scientific literature and to see connections between disparate subjects, generate new hypotheses, and suggest new experiments. If those experiments could also be run via computer simulations, then future iterations of ChatGPT could instantiate the necessary compute resource, write the code to run the simulation, analyze the results after the simulations finish, and then write the research paper for submission to Nature.

I don’t expect the role of the scientist to go away, but I do expect it to be greatly augmented by advances in AI. This has the potential to create a world where intractable problems are solved, diseases cured, and other sources of abundance created. But I suppose it will depend on how humanity chooses to use these powerful tools.

If you’ve enjoyed this post, take a look at our other articles on TL;DR, and if you’re working on your own start-up in the science/research/technology space, we’d love to hear from you!