TL;DR Summary

The worldwide COVID pandemic was a crisis unparalleled in recent history. The efforts of scientists and researchers around the world in mobilising to find vaccines, treatments, and explanations were equally unparalleled. In this article, we tell the story of one such research collaboration using their collective expertise in protein-modelling to help build a picture of the SARS-CoV-2 virus structure. Moreover, using modern collaborative writing tools, they were able to write up and publish their work during the height of the pandemic.

Background

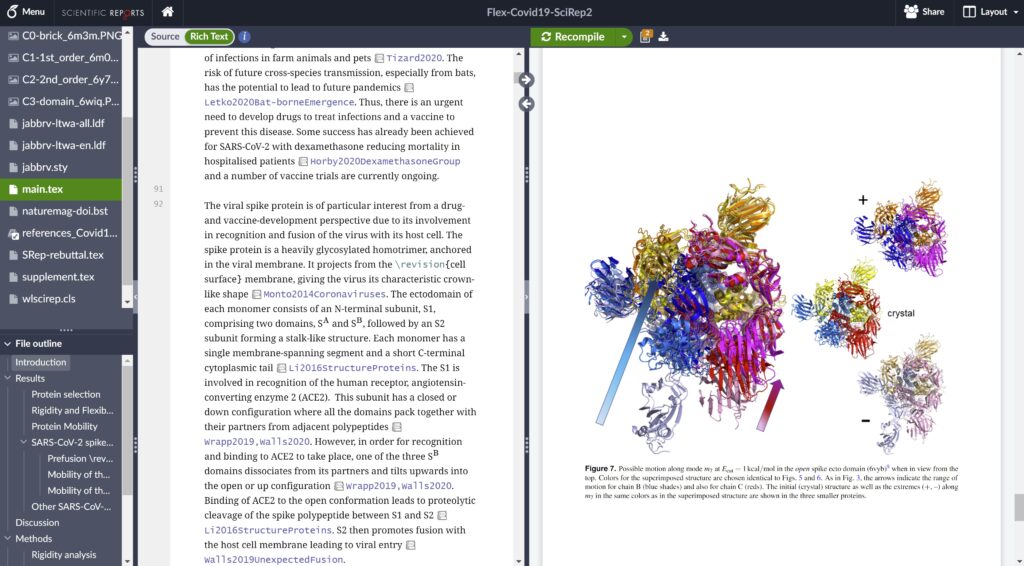

When COVID hit in early 2020, many researchers switched to working on COVID-related research. Professor Römer, a theoretical physicist, was working on a computationally intensive machine learning collaboration in France before returning to the UK ahead of lockdown. Unable to continue his work remotely, he realised his prior experience in protein-modelling could be used to assess the protein structures related to the COVID-causing SARS-CoV-2 virus. By refocusing on this aspect of his research work, he and his collaborators completed their analysis in four months, and their resulting paper was published in February 2021 in Nature Scientific Reports.

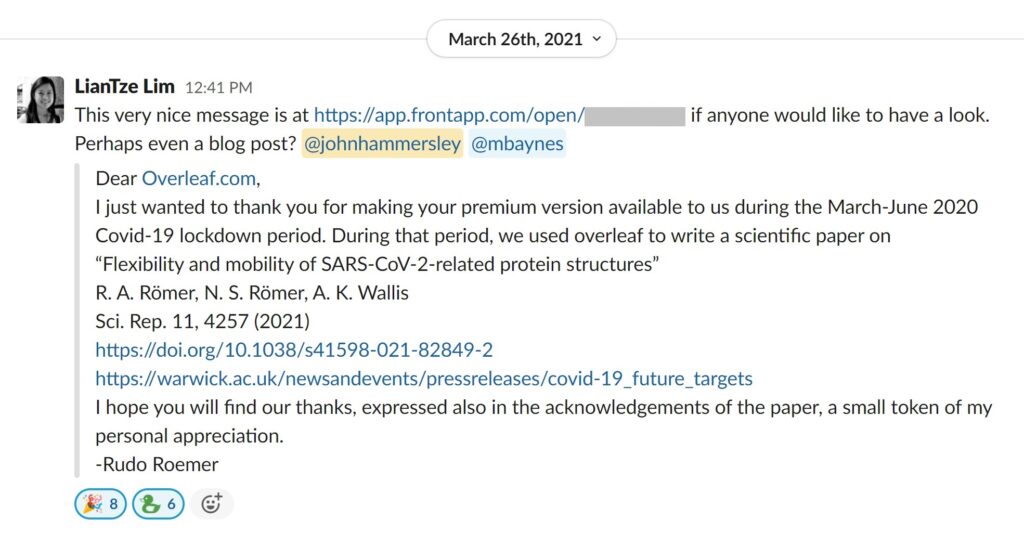

In order to write up their work quickly and effectively, while stuck in their respective homes like the rest of the population, they used Overleaf, an online collaborative writing tool based on LaTeX (of which I’m the founder!). After publishing their paper, Rudo wrote a note of thanks to the Overleaf team, as we provided free upgrades during the early months of the pandemic which had helped decisively with their write up. Lian Tze passed Rudo’s message on to me, I followed up with him and we got together over Zoom for a chat – resulting in this article 🙂

So, without further ado, here’s the write up of my interview with Rudo in full, originally recorded in April 2021.

To start us off, how did you find yourself working on COVID-related research?

For a number of years I was working, parallel to my “day job” on disordered quantum systems, in collaborations with colleagues in life sciences – using protein modelling to understand better the molecular mechanism underlying diseases such as HIV and Alzheimer’s. Briefly, the flexibility of proteins can be the cause of diseases, and understanding them can lead to better medicines and treatment. But as these protein molecules are tiny, about one ten thousandths of the width of a human hair, experiments are difficult. In such a situation, computational modelling of protein flexibility and dynamics can be an invaluable tool to gain understanding quicker and to help build some evidence of possible movements.

I was on sabbatical at CYU Cergy-Paris when COVID hit. As lockdown started in France, I decided to come back home, rather than remain in Cergy. Upon returning to the UK, what I was planning to do in France was no longer possible – it required use of GPU hardware based in my lab in France, and our remote connections to it were too slow. So we had to drop all the machine learning work. At the same time, there was clearly the motivation to use the tools that I had, as a physicist, to contribute to the worldwide effort in understanding the mechanisms by which COVID was spreading in our bodies. Since I knew how to model proteins, this was an obvious route. But…

“I’m a physicist, I don’t necessarily know what’s biologically relevant … so perhaps let’s just take all of those related to COVID into our computational model…”

As it turns out, pretty much from day zero of the COVID pandemic, structural biologists had begun to decipher the protein content of the SARS-CoV-2 virus – and then deposited their findings in the worldwide accessible Protein data bank (PDB, https://www.rcsb.org/). We searched the PDB for those proteins related to COVID and analysed their rigidity and flexibility to understand the basic lock and key mechanisms. This flexibility – open and close – is important, as it can affect where other molecules, such as potential treatment drugs, can attach. Readers might recall that the SARS-CoV-2 “spikes” are a very prominent feature of the COVID virus. We found, e.g., a possible such opening and closing mechanism at the top of the spikes, precisely where the virus attaches to the cell wall of a human cell to inject its viral load.

At https://animol.warwick.ac.uk/view/animol/33zu6q/1 one can see this opening and closing movement at the top of each spike visualised.

Who else were you working with on this?

Well, as it happens, my daughter is also on the paper! She’s a biomed student and helped me immensely with all the biology aspects and terms; I couldn’t have done this without her! For me, a protein is just a complex molecule, while she can understand the information provided in the PDB about the biomedical function of a particular protein. In previous years I would always have had a life sciences colleague working with me, but at home during the pandemic I didn’t have that. After a few weeks, when it seemed like we might have something worth writing about, we contacted Dr Katrine Wallis, an expert in protein biology, who joined us in the collaboration to provide the all important sanity check of our results since she understands if a flexibility in a certain region of the proteins might correlate with their molecular function. We made a good team, brought together by the pandemic.

You mentioned writing up your paper on Overleaf – why use Overleaf?

I’ve been using Overleaf for many years – probably five years or so – and was introduced to Overleaf by my then PhD students.

Previously I was still always using LaTeX, but with CVS / subversion for version control. However, these locally-based version control systems were challenging to use with collaborators. Most of my work involves research projects with international colleagues, many across Europe and the US, but also with India, China, Brazil, Korea, and Japan, and it was hard to find a platform that suited all.

How did working online help with these collaborations?

I can immediately see what other collaborators are doing, and as we have a premium Overleaf subscription, we can also look back (via the Overleaf project history) on what each other has added or removed. This made a real difference – previously it was much harder to keep track of what changes people had made.

We can also easily share images – by uploading directly to the project – whereas previously we’d probably have sent these back and forth by email.

Overleaf also helps lower the barriers for those just starting out with LaTeX, or those new to writing papers, such as PhD students. Indeed, we now routinely direct our undergraduate students to use Overleaf to write their final year projects.

In my research group, we’re also using Mendeley to share research between the groups – and the integration with Overleaf is marvellous.

And out of curiosity, how did you work with LaTeX previously?

I’ve been working in the research business for 30+ years, and have used LaTeX for all of that time. One of the early advances was in reference management – we started with a .bib file and put it on subversion to share it. We then tried jabref and others as new tools were developed, and when Mendeley came out, it ticked all the boxes as it worked across all operating systems – Linux, Macs, Windows, Android (although they now sadly seem to have dropped android support!).

Being able to use Overleaf on any (operating) system was a similar game-changer. Because people just need a web browser to access it, it can be used from anywhere – whereas previously one needed to have a local copy and keep it synchronised. With international collaborators, this often led to problems simply setting up a package environment where TeX libraries were similar and similarly uptodate. I also don’t have to think about downloading packages – I never have any issues with packages on Overleaf, it’s all handled for me. And although I don’t write papers on a tablet, it’s helpful to be able to view them on that sort of device whilst travelling.

What’s next in your research?

We have already done a follow up study on some of the various variants (alpha, beta, gamma, delta, etc.) and we are hoping to see whether the flexibility could be used as a marker distinguishing infectivity. Our results thus far indicate that the overall motion of wild-type and mutated spike protein structures remains largely the same (DOI 10.1088/1742-6596/2207/1/012016). Since the spikes are basically the prime functional target for all existing vaccines, our results provide reassurance that, at least from a flexibility approach, the geometry of the vaccines needs no major readjustment to continue to work also for the mutations of the spikes.

The paper was of course also written using Overleaf 🙂

Why don’t you just use MS Word?

Well, for me Word is ok for 1-3 page letters, or rough notes. But if you have a structured report, LaTeX beats it all. My daughter is writing her final university report in Word, and figure placements are all over the place, it just can’t control it the way LaTeX can. LaTeX – just does it, just does the job, at least to a level that then a professional editor can continue with final in-print adjustments 🙂

Ok, you’ve convinced me! What would you like to see on Overleaf in future?

You want to open these floodgates? Ok, since you asked:

- File management on the left is a bit bulky / clunky. Can’t click more than one file to take action. Please fix this!

- Uploading is fine (.zip upload would of course be welcome), but it’s frustrating you don’t have previews for .eps figures.

- Sometimes when right-clicking you don’t always have all the options one might expect.

- For my lecture notes – each chapter has its own tex file; it would be nice to be able to see that in its file structure (the \includes \input).

- Link sharing is good. Allows me as account holder, to invite large international teams to contribute.

- History – labelling is good. But quite often we seem to lose the “download project at this version” option because we are looking at the wrong view.

- Version compare is good.

- Chat is good, use that sometimes, especially with students. Otherwise have to fire up e.g. Teams.

- Also I like it that I can see when and where others are logged into the project (and we see the initials icons).

- Integration to the ArXiv could be better.

Overall it’s great — it’s simple to get students started on LaTeX, we just point them to Overleaf 😊

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article and would like to chat to us about featuring your research, founder story, or other interesting topic, please let us know — we’re always happy to hear your ideas and suggestions! Or just ping me on Twitter / LinkedIn 🙂