A generational shift in reverse

For decades, societal barriers have gradually lowered to enable more women to publish academic research and pursue a career in research. In 2021, for instance, women even outnumbered men in the reception of Doctoral degrees at US universities (Perry 2021). In some countries, it is even common for a woman to have a child while doing her PhD (the question being how many, rather than if); suggesting that motherhood and an academic career may be compatible providing the right environment.

Despite constant progress, we know that women have been disproportionately affected by the COVID-19 pandemic (Kwon, Yun, and Kang 2023); which had been anticipated a year earlier in a call by researchers to funders and institutions to address the likely fallout (Davis et al. 2022). So has the pandemic halted or reversed the progress women have made entering academic research?

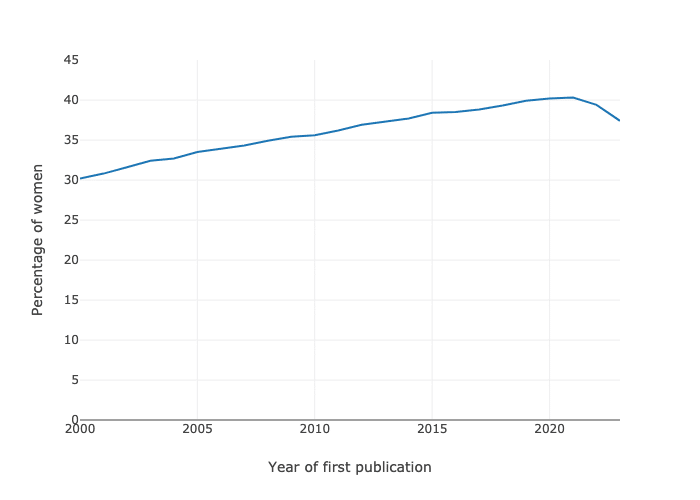

Global trends from 2000

Kwon et al (2023)’s analysis suggested that mid-career women and those living in less gender equal countries would be the most affected by the COVID-19 pandemic – but what about early career researchers? I set out to investigate how the proportion of women in the first publications had changed over time.

I started the analysis in 2000, using Dimensions.ai data in Google Big Query (GBQ) and Gender API data, which classifies gender from first names, using their probabilities to be used by a man or a woman. Metadata of research articles have changed since the 2000s; authors and journals at the very start of the period often recorded initials of authors, with women more likely to use them in order to hide their gender. If possible, Dimensions algorithms will have consolidated a profile with publications that had initials only and the first name, making it possible to track it in our analysis, but for women at the start of our period, especially those with a short career, it is possible that their gender is under reported. On the other hand, women would often change their name at marriage / divorce, making it impossible to track their profile if they had published before and therefore creating multiple “first publications”.

During the year 2000, 4.5 million women published their first academic publication, representing 30.2% of observable researchers. By 2021, the percentage of debut works authored by women had increased by a third, reaching 40.3% researchers (17.6 million of women). This increase can be attributed to a greater percentage of women starting a research career, and to a much lesser extent, the effect could be intensified by our inability to identify women accurately at the start of the period.

But 2022 and 2023 saw a downward trend, respectively to 39.4% and 37.4%, reaching 2013 values. This emerging downward curve signifies a generational shift in reverse from empowering girls and young women in academia to placing obstacles, intentional or not..

We know that in and outside of academia, women in countries around the world were affected disproportionately more than men by the COVID-19, but what about the first publications of those starting in academia?

Selected countries

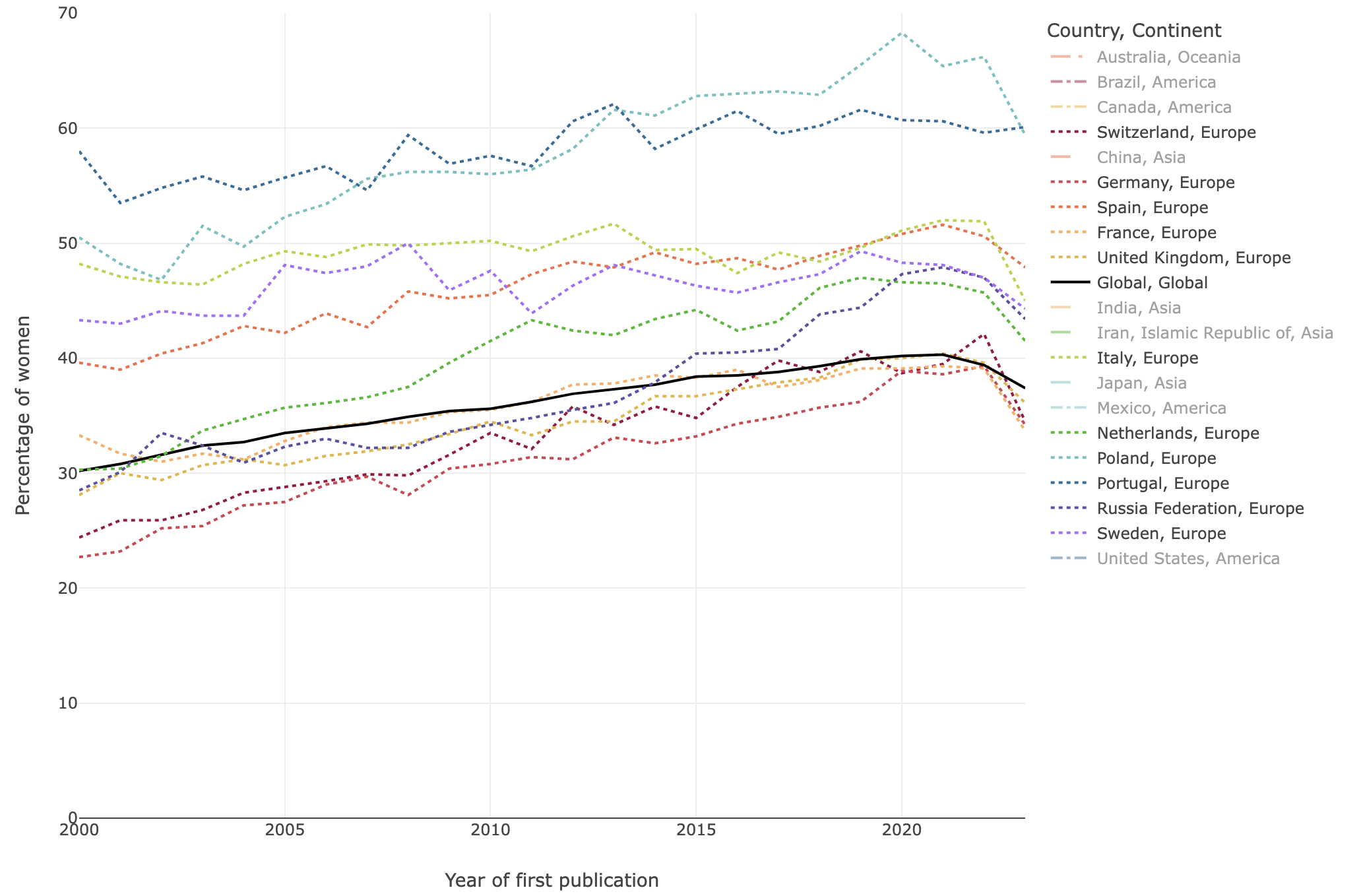

I selected the 20 countries with the highest number of women publishing their first publication over the period 2000-2023. The interactive graph below shows the trend over time, compared to global data presented earlier; double-click on one country to see only that one and progressively add the ones to be compared to.

Figure 2. Percentage of women who published their first publication between 2000 and 2023 in the top 20 countries by women’s first publications.

I then did a deep dive into three continents: Europe, Asia, and America, where countries placed themselves around this average.

European countries

Among the selected countries, the following countries were in Europe: Switzerland, Germany, Spain, France, United Kingdom, Italy, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Russia, and Sweden. Some European countries (Spain, France, Italy, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, and Sweden) stayed above or around the average, while the UK, Germany, Switzerland, and Russia* were below average during most of the period. All countries but Portugal observed a downward trend in 2022 and 2023.

* Slavic researchers use their initials more than others, making the determination of their gender more difficult.

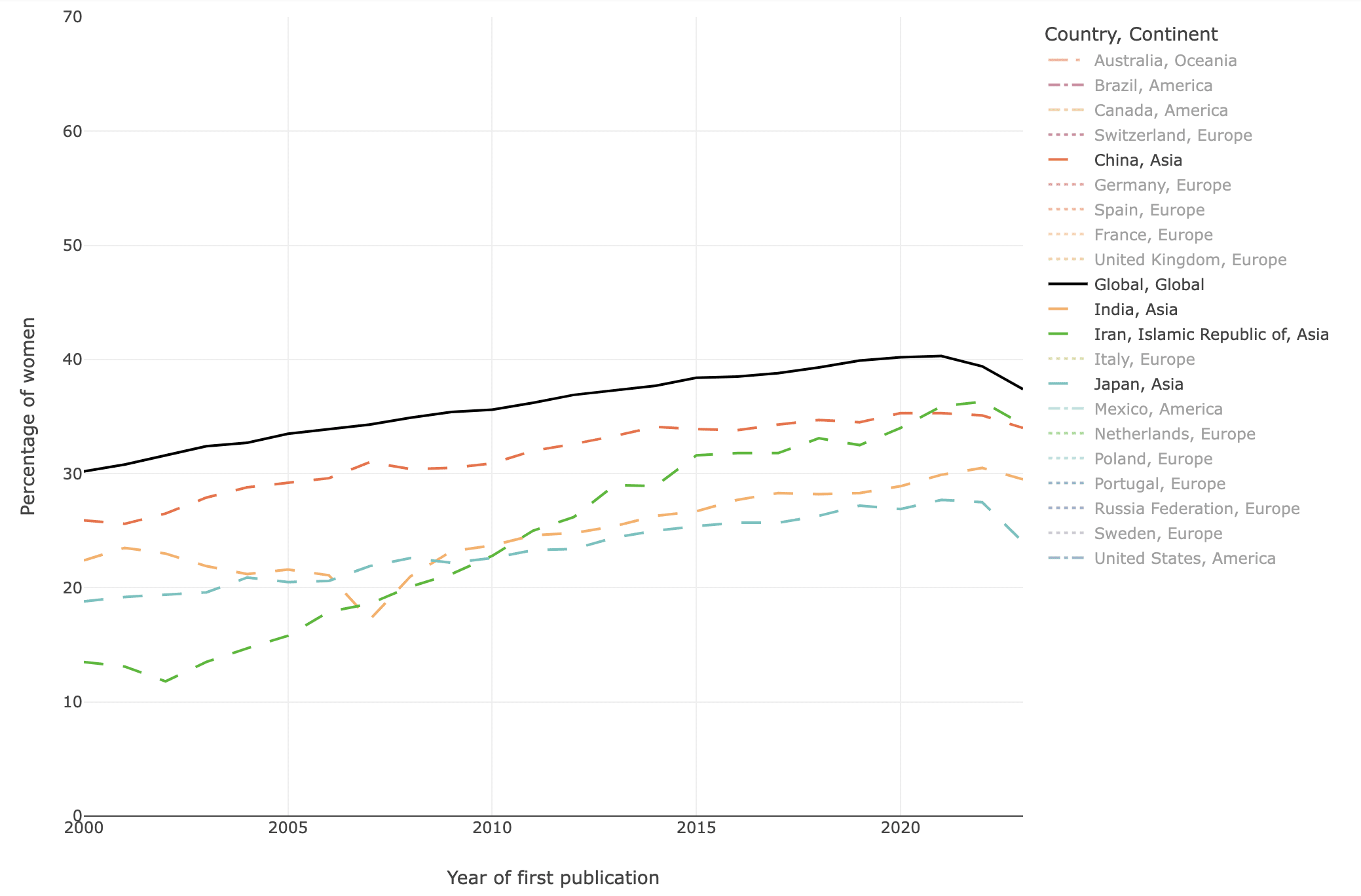

Asian countries

The four Asian countries (China, India and Japan) in the top 20 use non-latin transcripts and in general genders are more difficult to derive from Asian names, therefore our analysis cannot be as generalized as European countries. Nevertheless, for the names that could be analyzed, all Asian countries stayed below the global average over the period, India’s percentages of women’s first publication dipped in 2007. All observed a downward trend in 2022 and 2023.

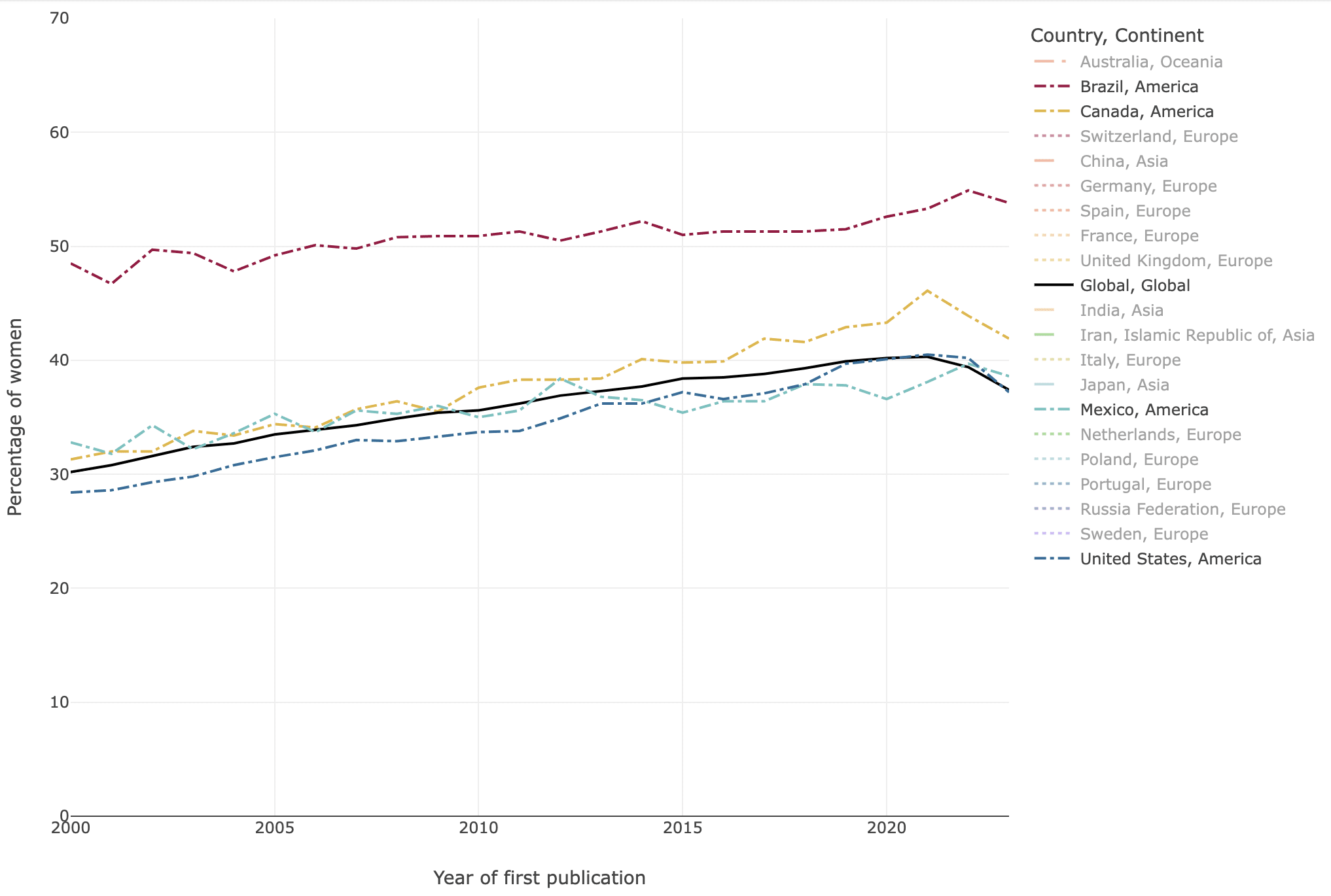

American countries

On the American continent (Brazil, Canada, Mexico and the US) on the other hand, all countries but the US stayed above the global average for most of the period. Brazil was even above the highest global value (40.3%) for almost the entire period. Mexico fluctuated above the global average until 2013, when it settled around or below the global average until 2022.

In search of the first grant

Dimensions also holds data on grants, albeit the coverage does not extend as fully as the publication dataset – it contains most established national and international funders but does not include all university and corporate grants. Nevertheless, I thought it might show a similar trend – so less publications would be related to less grants. In some fields, especially scientific fields, it is now common to write a PhD based on publication solely, while in others still write a thesis, and so the first publication would come during the first Postdoc.

However, the trend observed in the grant dataset was more mixed than the publication dataset – the grant dataset is smaller so it is more erratic, and although there is still an observable global decline of women receiving their first grant in 2022 and 2023, it is not seen in all countries. For instance, in the UK and the US, the proportion of women receiving their first grant has gone respectively flat and up. But it has gone down in the Netherlands (for which the representation of women in first publications was better than average), China and India.

Conclusion

The present analysis has shown that the long-term rise in the proportion of women publishing their first academic work has unexpectedly peaked in 2021, followed by two consecutive years of decline. The decline coincides with the COVID-19 pandemic and its immediate aftermath, which has affected society in general, but women more markedly.

I see two possible reasons for the decline of first publications: the decrease of less established grants, those that are not tracked by Dimensions (university or under another larger project) and / or the two-body problem. In the two-body problem two researchers attempt to find a place in the same university, which is often solved by one partner taking a lesser position in the university with more teaching than research, or lots of travel, which became harder during the pandemic.

However, if the trend persists, there is likely an on-going crisis and the change of trend since 2021 should be taken seriously. Data for 2024 showed a persistent decline but was not included in the analysis as the year has barely started (although in terms of publishing data, 2024 started in October 2023 when 2024 started appearing in Dimensions and we already have 200,000 women’s first publication in Dimensions).

The present analysis of the reversal should serve as a call-to-action for funders and institutions to support and retain women in research through and beyond times of crisis.

Bibliography

Davis, Pamela B., Emma A. Meagher, Claire Pomeroy, William L. Lowe, Arthur H. Rubenstein, Joy Y. Wu, Anne B. Curtis, and Rebecca D. Jackson. 2022. ‘Pandemic-Related Barriers to the Success of Women in Research: A Framework for Action’. Nature Medicine 28 (3): 436–38.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-01692-8

Kwon, Eunrang, Jinhyuk Yun, and Jeong-han Kang. 2023. ‘The Effect of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Gendered Research Productivity and Its Correlates’. Journal of Informetrics 17 (1): 101380.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2023.101380

Perry, Mark. 2021. ‘Women Earned the Majority of Doctoral Degrees in 2020 for the 12th Straight Year and Outnumber Men in Grad School 148 to 100’. American Enterprise Institute – AEI (blog). 14 October 2021.

https://www.aei.org/carpe-diem/women-earned-the-majority-of-doctoral-degrees-in-2020-for-the-12th-straight-year-and-outnumber-men-in-grad-school-148-to-100/