“It may take a militarily powerful nation to establish a language, but it takes an economically powerful one to maintain and expand it.”

David Crystal.[1]

A short commentary

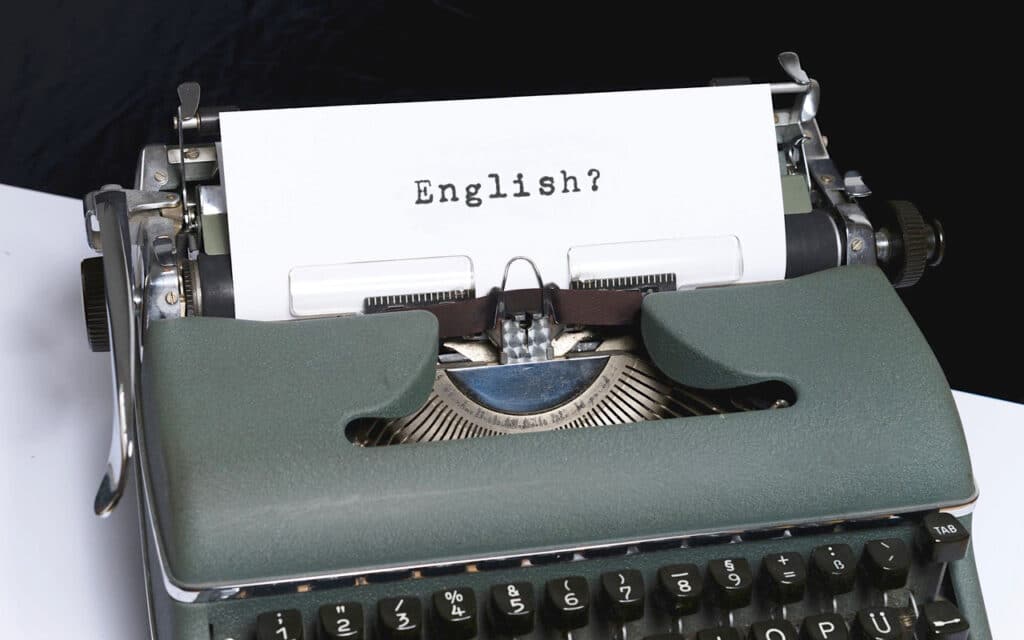

In this short opinion piece we look at English as the universal form of communication in science, in fact, the language of both science and technology.

Although many countries still publish journals in their native tongue, English is currently still the ‘best’ way to share research findings with scientists in other parts of the world.[2] However, from a historical perspective, this has not always been the case. Egyptian philosophers and stargazers told stories in hieroglyphs. Aristotle and Plato wrote books in Greek, which were then translated into Arabic by their followers. Then came the Romans, who wrote in Latin. It was not until the 20th century that English started to dominate.[3]

English as today’s global ‘lingua franca,’ is the language most widely spoken throughout the world even though the vast majority of English speakers are not ‘native’ speakers of the language. Of approximately 1.5 billion people who speak English, less than 400 million use it as a first language which means that over 1 billion speak it as a second language.

With today’s technological advances, English as the global language of science and innovation could change by reducing the need to learn English as a language for international communication. AI language tools are becoming increasingly sophisticated and AI-powered translation could potentially create more fair access to science.[4] Moreover, the rise of China’s research productivity and published research output could have a big impact on how we communicate science.[5] The bias, if it can be called a bias, towards the use of English in the current global scientific landscape, however, can lead to barriers for those who are non-native English speakers and also to important research study outcomes being overlooked because they are not written in English.

“With today’s technological advances, English as the global language of science and innovation could change”

The consequences of overlooking non-English science may be more serious than just revealing a lack of access to information written in languages other than English. For example, in a study published in PLOS[6], it was identified that important papers reporting the infection of pigs with avian influenza viruses in China were initially going unnoticed by international communities, including the World Health Organization and the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. This was because they were published in Chinese-language journals[7]. Likewise, in one of the non-English scientific papers it was reported that “urgent attention should be paid to the pandemic preparedness of these two subtypes of influenza”[8]. It took 14 years for this finding to be picked up and reported on in the English language.

In a 2021 study, Plos Biology screened 419,679 peer-reviewed papers in 16 languages in the field of biodiversity and found that non-English-language studies can expand the geographical coverage of English-language evidence by 12% to 25%, especially in biodiverse regions. As with the study in the previous paragraph, the authors of this study urge wider disciplines to reassess the untapped potential of non-English-language science in informing decisions to address other global challenges.[9]

Today the populations of native speakers of other languages are all growing faster than the population of native English speakers. About three times more people are native Chinese speakers as are native English speakers. Languages such as Hindi-Urdu, Arabic, Spanish, to name a few, are about the same as those whose native language is English, all of which are growing faster than native English speakers.

Many scientific papers go unnoticed because of the linguistic gap between the global north and the south. English has become the lingua franca of science to ease collaboration but has it really managed to do so? In fact the dominance of the English language risks excluding some of the global south countries.

Digital Science, as the creator of the world’s largest linked database for research information, Dimensions, is able to search the data it holds to find the language in which research publications are written. This is done using an algorithm to detect the language of publications.[10] The total number of research publications currently stored in Dimensions is 139,644,299 and the table below highlights the probable numbers and percentages of publications in the top six languages of publication along with the number and percentage of publications where no language is detected. The total number of research publication languages in Dimensions is 148, ranging from a language with one publication to the highest numbers of publications set out in Table 1 below.

| Probable* number of research publications stored in Dimensions | Probable* percentage of total research publications stored in Dimensions | |

| English | 114,714, 760 | 82% |

| German | 5,717,480 | 4% |

| Japanese | 3,465,074 | 2.40% |

| French | 3,11,7238 | 2.20% |

| Portuguese | 1,659,218 | 1.18% |

| Spanish | 1,646,606 | 1.17% |

| No language detected | 1,584,716 | 1.13% |

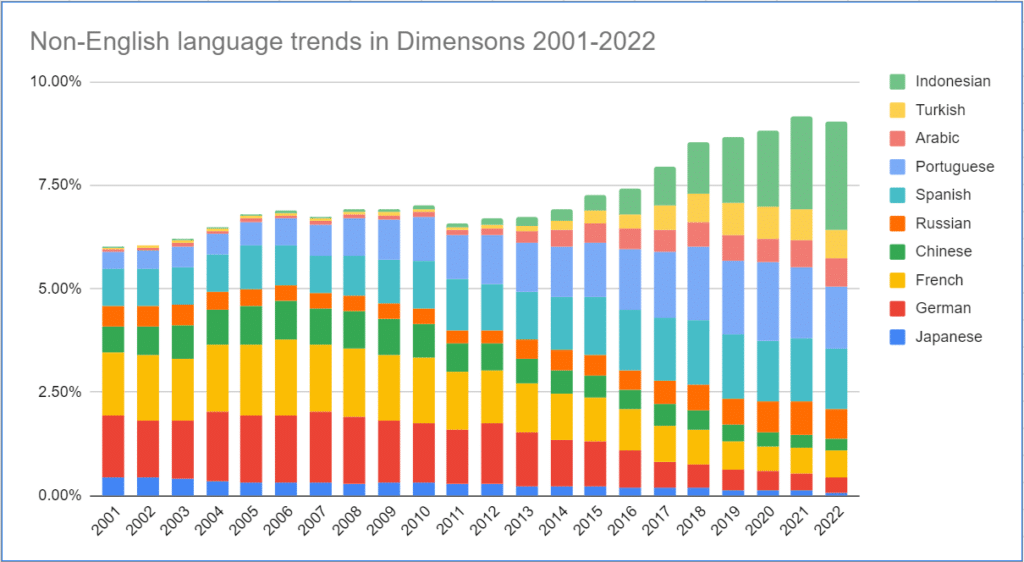

We also looked at trends over time (2001-2022) for the the top ten non-English language publications sourced from Dimensions (see Figure 1 below).

The top 10 non-English language publications and the percentage overall, show that a number of the top languages in the 2000s (in particular, French, German, Chinese, and Japanese) have waned in the 2010s; whereas others (Russian, Spanish, Portuguese, and especially Arabic, Turkish, and Indonesian) have increased significantly.

In terms of non-English language research coverage in Dimensions (at least for the sum of the top ten 10 other languages), there has been a growth within the publications corpus from circa 6% in 2001 to greater than 9% in 2022. We might conclude here that there is either an effect of more non-English research being indexed by Dimensions or that there are beginning to be signs of researchers publishing in their own language when it is other than English.

“Perhaps it is time for the scientific world to acknowledge and embrace work published in all languages to help diversify science thereby enriching research globally.”

Conclusion

As we outlined, the language gap between the Global North and Global South is likely to have excluded much of the research in the lower income countries. As long as English remains the language for scientific communication, many people of other cultural backgrounds will continue to find it increasingly difficult to participate in the scientific process and benefit from its outcomes.[11] With regard to patterns of non-English publishing over time, we cannot rule out that the increases that we see are not a product of Dimensions amassing more non-English research output, but, at the same time it could be that publication patterns have made shifts to digital and/or open access publications that have affected what is included in the Dimensions database.

Perhaps it is time for the scientific world to acknowledge and embrace work published in all languages to help diversify science thereby enriching research globally.

Acknowledgement

Thanks to Alex Wade, VP Data Products, Digital Science, for providing time trends data and graph.

References

[1] https://culturaldiplomacy.org/academy/pdf/research/books/nation_branding/English_As_A_Global_Language_-_David_Crystal.pdf

[2] https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-00899-y

[3] https://scientific-publishing.webshop.elsevier.com/manuscript-preparation/why-is-english-the-main-language-of-science/

[4] https://www.nature.com/articles/s41562-023-01679-6

[5] https://scientific-publishing.webshop.elsevier.com/manuscript-preparation/why-is-english-the-main-language-of-science/

[6] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7094971/pdf/41586_2004_Article_BF430955a.pdf

[7] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7094971/

[8] https://europepmc.org/article/cba/580966

[9] https://journals.plos.org/plosbiology/article?id=10.1371/journal.pbio.3001296

[10] Algorithm available on request.

[11] https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2020.00031/full